Behind the scenes of getting to a tech transfer agreement with your university (2/4)

Checklist of questions to consider for your specific case

This is the second post of a four-part series: The first post was about the main elements of what is called a tech transfer agreement, including some concrete examples and sources for reference values and terms. In this second post today, I will discuss essential questions to keep in mind when negotiating your specific terms. In a third post I will take a closer look at the underlying incentives and organizational structures at both universities and startups - to help you understand each other better as negotiation partners. A final post will help to look at some typical arguments you might be faced with in the negotiation and where they are coming from (and how to respond).

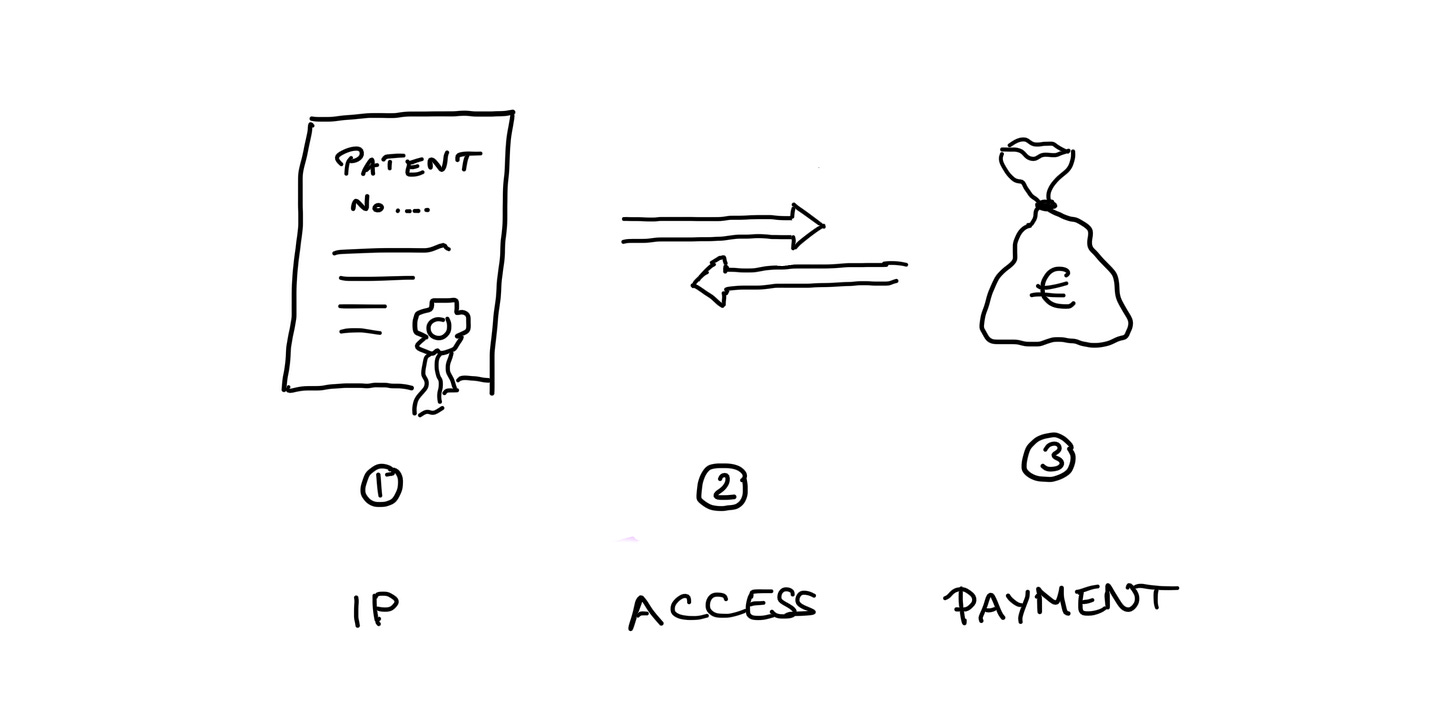

In the first post, I gave an overview of the three main components a tech transfer agreement is made up of. To recap, those are:

1. 🧠 - The exact IP you want to get access to:

2. 🤝 - How you get access to the IP (the structure of the agreement):

3 💰 - And what the university or research institution gets in return for providing access to the IP

What is ‘good’?

After looking at some high-level corridors and discussions about standard terms in the last post, the question still stands: how exactly does a good deal look like for you? What should you strive for? Today, I want to share a number of questions (use them as a checklist to consider if you want!) that help you evaluate for yourself if the deal you are negotiating is ‘good’ for your case.

First things first: As you can imagine, there is no one-size-fits-all answer. At Positron, we have seen (but not invested in) everything from deals with 0% equity, low single digit royalty payments and the option to buy out all the IP for a six-figure amount after hitting certain milestones, as well as deals that consist of an equity stake of +/- 20% and no other payments. And if you take a look at this database (data from 200+ spinoffs in Europe), you’ll find a myriad of other combinations. Not necessarily all good though.

What is good depends a lot on the value of the IP for your individual company and the potential future partnership agreement you might enter into with the university. Most discussions revolve around universities taking too much equity - but this is really only one possible aspect of the agreement that can go wrong (or well!).

Key questions to ask yourself with respect to the different elements

Some potential questions (including some potentially controversial opinions) to consider when negotiating your agreement (with regard to each of the above three key parts of the agreement) that might alter what ‘good’ means in your case:

1. 🧠 - The IP you get access to:

What IP are you trying to transfer? Is it one smaller patent or a whole patent family? Is it access to a certain dataset?

How core is the IP to your startup’s success? If you look at your future business model: what role do the elements building on the IP play in the overall business case?

Can you circumvent and improve upon your own IP (i.e. do you really need access to the patent)? This might be an option in some cases.

What other IP would you like to have access to in future? For example, will you get the option to later license IP from the same research group at favorable terms (or have first right to it)?

2. 🤝 - The structure of the agreement:

Are you already set on needing the IP or would you like to ‘evaluate’ it first? Sometimes you might initially also only want the option to later license/transfer the IP. This often allows you to get cheap access to ‘evaluate’ the worth of the IP for your company and after hitting certain milestones either switch to a full license/transfer or waive your right to do so.1

How important is exclusivity to you? It is commonplace to assume investors want to see an exclusive license to the relevant IP. And most likely that is true at some point, but it does not necessarily hold true from day one on. Asking for an exclusive license, i.e. only you and no one else can use the IP in all industrial fields, can be pretty daunting to the university or research institution.2 They might have invested quite some money into this and now they are promising everything to an unknown startup that hasn’t even secured any financing yet. One tactic might be to only ask for a license for a certain field3 and add an option for a full exclusive license over time and a ‘right of first refusal’ clause4 into the contract. That way the university does not feel like it is giving everything away at once and you have full control to expand it if you need to (but maybe from a better negotiation position with more money raised or the original IP playing a less important role over time). With some universities, going for something not fully exclusive on day 1 can speed up the process.

Do you prefer a full transfer or license deal? Sometimes I hear that “you as investors will definitely want us to have full ownership of the IP, right?”, i.e. investors seem to be expecting the startup to own all of the relevant IP instead of entering into a licensing agreement with the university (with the university still officially owning the IP). Personally, I do not see this in such strict terms. Of course, owning your IP is advantageous for you as a founder. However, licensing agreements (with the university or research institution remaining the owner) are way more common. It is the de facto standard in the US or UK and also more common at most European universities or research organizations that I have seen. It is important to consider, however, the license deal is structured, e.g. including the option to sublicense and ensuring that the rights to access the IP transfer in case of a sale of your startup to another company.

3. 💰 - What the university receives in return:

Valuing the IP:

Looking at the value of IP in comparison to others:

Who else is interested in the IP in question? Are you the sole negotiating partner with your university or are there others interested?

What costs have and will incur for the protection of the IP?

What can you compare the value of the IP to?5

Looking at the value of IP for your company:

How does the payment relate to what IP you are transferring?

How does the ‘payment’ relate to the importance of the IP for your business?

In case of an equity stake:

What value will they bring as a future shareholder? Are they participating as an investor? Do you have any additional agreements in place that are creating immediate or future value for your spinoff (e.g. around use of lab space, monetary support, future R&D collaborations)?6

Does the equity come with any special demands, e.g. anti-dilution protection or board seats?

In case of royalties:

Are they capped? At what height or after what duration? How do you see your possible revenues ramp up?

Other considerations:

What is more or less valuable to you: a clean captable but payments reducing your profits (no equity stake but royalties) or an additional stakeholder on board but no impact on your cashflow initially (royalties but no equity stake)?

Are you willing to trade lower upfront payments for higher royalties, or vice versa?

Consider different trajectories of your company: What would you be giving up in the best and/or worst case? What’s the minimum or maximum you will end up paying?

How does the IP cost relate to other costs you have and your necessary fundraising amounts?

4. Further questions to keep in mind:

How much does the speed of reaching an agreement matter to you? What are you willing to sacrifice in terms of the terms to speed up the process?

Do you already have a (or several) first investors lined up? Consider getting feedback from angels or investors around you on proposed terms.

I hope this first overview and some questions to consider can help you plan for your tech transfer negotiation. In a next post (following soon), I will focus more on the actual negotiation patterns. I’ll also shed light on the underlying incentives and structures at both universities and startups - to help you understand each other better as negotiation partners and to give you a better grasp on where certain arguments are coming from.

Let me know if you have other examples of standard terms to share or questions that helped you consider your tech transfer agreement.

Share this with anyone in the tech transfer process right and look out for the future posts on this topic!

If you think your science is pretty cool but you are not sure yet if you are cut out to be an entrepreneur: let’s talk. E-mail me or join an upcoming 1:1 office hour for scientists.

If you know someone who you think has the potential to be a great scientist-entrepreneur (although they might not realize so yet themselves), reach out to me at scientists@positron.vc.

This is also a likely option in case the patents are only filed but not yet granted.

I’ll talk more about why this is the case in the next post.

For example, in the case of a biotech process just licensing the technology for the food industry but not fibers/materials.

‘Right of first refusal’ means it needs to be offered to you before they can up a licensing agreement with anyone else.

Valuing IP at such an early stage is inherently difficult. Two options to consider: Finding comparable examples (at your own university or others) or taking a very detailed approach such as suggested by a working group of German universities: https://www.sprind.org/en/articles/ip_transfer/

More thoughts on this in the next post, but consider asking other spinoffs from your university and learning how the university is actually providing value beyond incorporation.