Behind the scenes of getting to a tech transfer agreement with your university (4/4)

Common points of friction between you & the university - and: how to react

This is part of a four-part series: The first post is about the main elements of what is called a tech transfer agreement, offers concrete examples and includes sources for reference values and terms. Part two discusses essential questions to keep in mind when negotiating the exact terms. In a third post we take a closer look at the underlying incentives and organizational structures at both universities and startups - to help you understand each other better as negotiation partners. In a final post today, these different incentives will help to look at some points of friction that are bound to appear during the negotiation and how to think about them.

Negotiations between startups/founders and universities on starting companies and licensing IP can be fraught with accusations and misunderstandings. These surface in the different terms and conditions that both sides think are acceptable. I think we can get to a smoother negotiation if we understand the different sides involved better - the last post was an overview of different incentives and structures at startups and research organizations to do just that: understand each other better.

Now, let’s take a final look at the most common points of friction that arise due to these different incentives and structural setups - and discuss what we can do about them.

There are three key points where I commonly see friction arise: value creation, timelines and risk. Let’s look at each of them individually.

1. Value creation

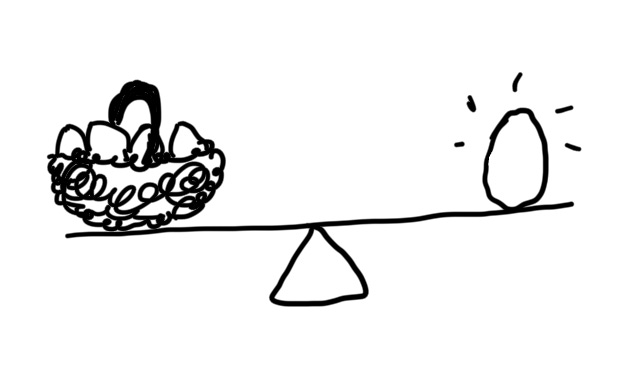

This misunderstanding typically revolves around the discrepancy between the question of "What value has been created so far?” versus “What is the road ahead, i.e. what value still needs to be created?”. The pattern that can be observed is that research organizations tend to overestimate past achievements and underestimate future growth needs. The research institution might say: “We have invested x million Euros into the development of this technology, that’s why we should own at least y% of the company”.

How to think about this:

First of all: yes, a lot of value creation has happened at the research institute so far, otherwise you would probably not want to start this company. Something has been developed that is core to building a new company and there should be a way to compensate for that.

At the same time, all you have at this moment in time is a scientific advancement, hopefully protected by one or several patents, and a lab proof of concept. There are no actual products, no pilots, no customers, no production sites or manufacturing or sales teams. A whole organization is waiting to be built. And with regard to all of that the initial IP will likely play a much smaller role than expected.

Imagine a piece of IP that covers optical sensors that allow for new imaging technologies in nano satellites. You get the patent for that. You’ll then probably need an engineering team that optimizes this IP for the use in satellites, you might have to build up another team building the right satellites for your use case, you’ll build up a data/software team to analyze the created data and build a product for customers to use, a business development/sales team will need to find the first pilot partners and customers, a partnership team might be negotiating launch possibilities for your satellites, you’ll set up internal operations (HR, Finance,…) to make all the other teams function smoothly,… Lots to do. Lots to do to actually create value from the initial IP.

A way of putting this into numbers and making this tangible in the discussion with your TTO could be:

Start by taking a look at ‘what has been put in so far’, i.e. the R&D expenditure. As an example, let’s take 2m€. And set this to resemble more or less the value today.

Then jointly discuss ‘what we think this could be worth if widely successful’. What are other companies in this field worth, what’s the market size, what are we aiming to achieve? For example, do we (university & startup) agree we could become a - in the startup world widely popular - unicorn, valued at 1bn€?

Now compare the gap between the value put in up to today and where you still think you can develop to, e.g. the 2m€ to the 1bn€. Quite a gap. That implies there is still a lot of value that we need to generate, right? So the initial 2m€ aren’t actually that big of a puzzle piece after all. And the equity should resemble that. This doesn’t mean 0.2% (2m/1bn) is the ‘correct’ value to agree on, but at least it should pose an argument against 20% being a fair equity share to compensate for the IP.

Overall the cap table, i.e. who owns what part of the company, should be a reflection of who contributes how much to the future anticipated value. In an ideal world all parties on the cap table play an active role in creating future value for the company. Co-founders as knowledge owners building the product and company; investors, angels or advisors as multipliers to find customers, partners or future capital. Ask the research organization: what role will they play in future value creation? Will they be able to help you find investors or customers in two years? What role will they play in the process of product development, manufacturing or sales? Yes, there are cases in which the university actually plays a strong role with well-aligned R&D activities or a smaller role with lab space and initial mentoring in the first months. But be careful and consider what value you think they will really play down the line.

Similar arguments that might pop up in this context:

The research institution says: “Having our brand name on your shareholders list is worth quite some equity.”

Questionable. Are they going to play an active role? A pure name on a cap table of someone that is not actively helping build the company (through whatever means) has rarely convinced an investor. Double-check this with prior founders from your institution and angels/investors/future partners. This might be the case for some institutions. But going back to the point I made earlier: how valuable are they really in future value creation? A pure university brand name won’t help here.

The professor or department head says: “Oh, this was created in my lab. I should definitely also own x% of this company.”

Unfortunately, I have seen this several times where people in the vicinity of the created IP want shares, and not at low percentages (I’ve seen asks between 10-20% for people that will stay in academia full-time and have no operational role in creating the company). Similarly to the above argument for universities: how much value are they going to create down the line? It is not unheard of to give some of these people (very) low single-digit percentages in equity if they also play a role as a future advisor, have great networks, you want to keep an R&D (thought) partnership with them alive, etc. But don’t give away 10+% to non-operational people. Guard your equity.

Recommendations:

For the research organization:

“You don’t get rich by being greedy.”1 Taking too much (no matter if it’s equity or licensing fees) early, will hinder the future growth of the company and reduce potential future value.

Create transparency about your role and professionalism as a shareholder. How will you contribute to the future growth of the company?

For the founder/startup:

Create a future vision of what your startup will aim for. And get concrete about what it will take to get there.

Achieve alignment with future shareholders around the explicit contribution of each to that future vision.

2. Timelines

In terms of timelines to success (aka when does the IP transfer return an investment), there is often an imbalance between short and long term incentives.

A typical pattern I observe is that at a research organization there can be a bias towards the question of “what/who pays the bills tomorrow?” versus at a startup the ability to pay back the investment might be many years into the future.

There are slight differences between different types of organizations however. Try to understand where your organization stands on this:

In most public research organizations the incentive structure rewards short term money acquisition (either in terms of public grants or immediate license fees from industry). That means any quick money made by a corporate paying license fees today is always worth more than elusive and improbable exits or royalty fees from a startup down the road.

Universities often have more of a public benefit goal as in “it’s our mission to give back to society and therefore commercialize our research”. But again, they might have limited budgets for tech transfer offices and filing and holding IP. Sometimes just covering those costs is a primary need. Additionally, as mentioned before, they might lack the structures to hold equity at all.

Possible implications that this mismatch can have for the tech transfer process:

Your ability to even spin out at all. A lot of times, it is tricky to even be allowed to spend time on a potential spinoff at all, because there are limited resources assigned to tech transfer and you are trying to work on something that is not paying the institute’s bills tomorrow.

On the research organization’s side this might lead to a preference for early milestone payments instead of license fees or equity shares, i.e. paying back patent costs accruing today compared to potential but uncertain future paybacks.

On the startup side this will likely lead to a preference for later equity or license fees - due to scarce cash in the beginning. You will want to spend all the limited resources you have as a startup on creating, establishing and selling a product and actually creating a viable business. While limiting the money flowing back to the university at an early stage.

In terms of decision making timelines the speed is likely reversed: now the startup cares most about tomorrow, the research organization has no problem operating in months, quarters or years.

Recommendations:

For the research organization:

You can’t have both: a potential upside in future and cash in the bank tomorrow. You’ll need to be clear on what is more important to you and what you are willing to trade in for that (e.g. no participation in a future upside but patent expenses and TTO costs covered tomorrow, meaning you will have to work within the amounts an early stage startup can afford). Be transparent about why a certain setup (shares/fees/etc.) is relevant to you.

Evaluate the extremes: ‘no money now - only potential upside in a future exit’ (high risk but possibly higher reward) vs. ‘expenses covered now - no upside in the future’ (low risk but then you might be ‘underpaid’ to what the IP is worth in your eyes).

For the founder/startup:

Yes, you likely don’t have much cash initially, so a future payment (via royalties or equity) feels more doable, but consider the benefits of early milestone payments: a ‘cleaner’ cap table or less royalties to pay down the line. Calculate best and worst case scenarios, what’s the minimum or maximum you are giving up in either case (and what’s the risk associated with it).

And: how do these different values fit to your remaining financing needs? If early milestone payments are an option, what share of your financing round would they make up? This can also help anchor certain values with the university.

There is no ‘too early’ to start talking to your research organization. A research organization is used to taking decisions in different timeframes. A first VC or angel investor will likely only invest once the tech transfer agreement is signed, so don’t wait for your fundraising process to start before you talk to the university. But do involve your potential first investors in the process to make sure you end up with a deal that all initial parties can support.

3. Risk

This point of friction comes down to the simple truth that ‘the startup is likely to fail’. At the same time, the blunt truth is also, that (most likely) ‘there’s no one else doing this’ (i.e. commercializing this IP).

What I observe is that at a research organization there is a tendency to overestimate alternative commercialization paths for a certain piece of IP while underestimating the fact that this group of founders is willing to do something that no one else is.

Of course, you are certain that your startup is going to take off and be wildly successful. (And I wish you the best of luck!) However, the statistics are against you. Typical numbers will show a 90% failure rate within the first 3 years. Even if this is significantly lower for startups based on solid university IP, there is still a high likelihood that you won’t ever monetize the IP in question. So that is why a full transfer of the IP, especially early on before certain milestones are achieved, is rather rare. The university will want to keep some lever in place that in case your success is not as predicted they have a second chance to monetize this.

Now to ‘overestimating alternative commercialization paths’: sometimes I get the feeling that the assumption at the research organization is that if your startup fails, there will be countless other ways to monetize the IP, and your tech transfer agreement is in competition with this alternatives (i.e. we’ll just sell it to corporate x for y millions).

To counter that, ask the question ‘what’s the alternative to us commercializing this?’. Many times if you don’t get the chance to build a company - admittedly with an uncertain outcome and no guarantee of success - the alternative is not that the IP will be sold to a large corporation for millions, the most likely alternative is that no one else does anything with it. Why:

IP does not just sell itself. Unless the research organization is a very large organization with a dedicated team in place to monetize IP and actively find customers for it, this will be an immense battle. The research organization is very dependent on the respective researcher or research group finding customers for it. So if your startup doesn’t manage to do it, and you have all left the university by then, there most likely won’t be too many other eager people left to monetize it afterwards either.

In general, IP can roughly be said to fall into two categories:

Is it mostly improving existing products and processes? In this case it might make sense to create a startup but a valid alternative could also be that an incumbent incorporates the IP. In this case, there might be more competition around the IP/a potential Plan B if your startup doesn’t turn out to be successful.

Or is it creating a completely new product? Something where no obvious market exists yet or more proof of concept is needed before it can be released to the market: More likely to be a startup case and less obvious to be taken up by a corporation. A plan B if your startup fails is highly unlikely.

Possible implications that dealing with risk differently can have for the tech transfer process:

Negotiating a fall back option. Although, as I said, the alternative commercialization paths are likely overestimated, the research organization might want to have a fall back option in case you don’t end up doing anything with the IP.

Preferences for equity vs licensing deals: licensing will bring money back to a research organization as soon as there are sales while equity might be worth more overall but with an even longer and more uncertain time horizon. Licensing deals are thus less risky for the organization.

Portfolio risk: your risk as a founder is fully concentrated on your one startup and often this is the same for an institute (because they don’t do many tech transfer deals) which is why they are very prone to looking for high stakes or licensing fees to cover this risk. Ideally, if they supported many startups they could look at taking risks differently. Similar to a VC they could bundle the risk in a portfolio, i.e. if you do a lot of investments each individual risk is offset by the fact that others might be successful. It would be a nice side effect of institutions supporting more startups, that the overall risk reduces and they would need to guard for that less in each individual case (i.e. could live with smaller equity stakes or fees).

Recommendations:

For the research organization:

What are the commercialization alternatives really? Truthfully consider them. Who else is going to monetize the IP?

Instead of trying to cover all the risk that a startup comes with via higher stakes or fees, consider these two things to reduce the risk:

Shift to supporting startups as much as you can. Instead of making their transition slow and cumbersome, it might pay off more to speed your processes up, be fast, take a couple percentage points or Euros less initially, if you instead help them to get on path to success more quickly and easily.

Support more startups overall - and the risk of each individual one will be outweighed by the others.

For the founder/startup:

You can’t have it all either: a guaranteed job at the research organization and full upside in a potential startup. Choose your path and make your commitment to that route clear. If you don’t believe in the success of your startup and show that by going all in, why would the research organization believe in you?

Consider the alternative commercialization options - what is the upside of your route and are there even obvious other routes to compare your risk and reward to?

Some final ideas, strategies & comments for your negotiation:

Consider:

Learning from others: Talk to prior spinoff founders from your institution: what experiences have they made? What advice can they give? And if your institution has no prior experience at all, then your next best bet is finding role models in other places, maybe universities of similar size. I’m pretty sure they’ll be happy to help as they know how frustrating this might be.

Talking to investors early on: get your own ‘market price’ for the IP. What terms would the investors that you would like to have on board (now or in the future) agree to? They will most likely not invest before you have a signed agreement with the university but if they are excited about you, they’ll be happy to give you pointers to make sure the agreement you create is not an issue in future financing rounds.

Finding allies in the system, e.g. a department or institute head at your institution. It depends on who is the negotiator and who is the decision maker in your institution. But often times, although you might be agreeing on terms with a tech transfer office, the voice of a senior professor, dean, institute head will carry a lot of weight in such a discussion. They might also have a different (more strategic?) view on the matter at hand than the TTO itself. If you can convince others in the organization to put in a good word for you this can be hugely beneficial.

Timelines: start this process as early as possible. Unfortunately, counter to the short term timelines needed by the research organization in terms of payback, a research organization has likely no urgency to make a decision on a certain tech transfer, versus a startup needing decisions as quickly as possible or the market (potential customers, investors, etc.) may have moved on. So don’t hesitate to start this process as early as possible.

Hopefully these four blog posts on tech transfer can help you smoothen your own transition from research organization to startup. Write to me about any questions that arise that I haven’t covered, or other tips, resources and examples to share.

And share this with other scientists that might benefit from it!

If you think your science is pretty cool but you are not sure yet if you are cut out to be an entrepreneur: let’s talk. E-mail me or join an upcoming 1:1 office hour for scientists.

If you know someone who you think has the potential to be a great scientist-entrepreneur (although they might not realize so yet themselves), reach out to me at scientists@positron.vc.

Quoting Dietmar Harhoff here who recently said this on a Falling Walls panel: